UAP Personalities

Brown, Thomas Townsend

- Co-namesake of the “Biefeld–Brown effect,” linking high-voltage capacitors to a claimed gravity-related propellantless thrust.

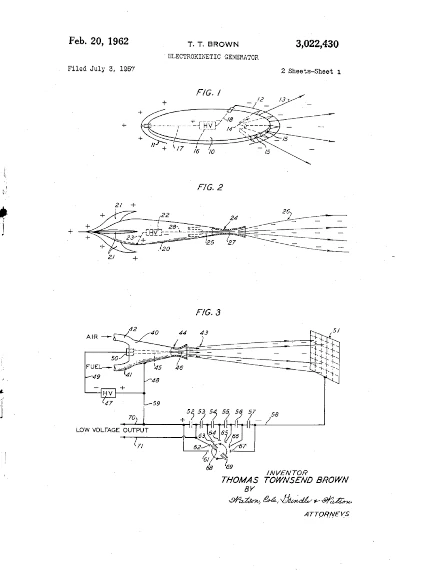

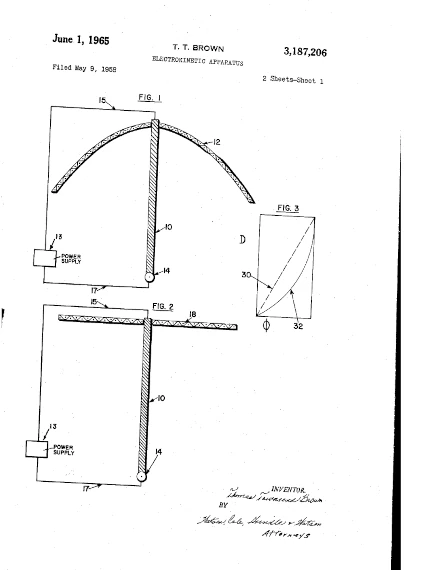

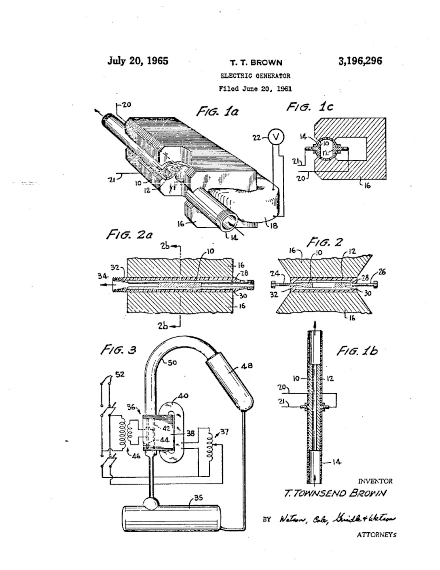

- Promoted “electrokinetic” / “electrogravitic” propulsion concepts for decades via patents, demonstrations, and proposals.

- Became a foundational figure in anti-gravity/electrogravitics mythology—often cited as evidence of suppressed breakthrough propulsion.

- One of his first BBE experiments used two 44lb lead spheres for electrodes and a glass rod as a dielectric in between them producing a thrust from negative electrode to positive electrode.

- Remains disputed: many demonstrations are argued to be ion-wind/electrohydrodynamic thrust rather than true gravity manipulation in spite of the fact ion wind velocities would need to be extraordinarily high to move 88+lbs of lead and glass like in his early experiment.

Introduction

Thomas Townsend Brown (1905–1985) was an American inventor and unconventional propulsion advocate most closely associated with the phenomenon later called the Biefeld–Brown effect. Beginning in the 1920s, Brown advanced the idea that high-voltage electrical systems—especially asymmetrical capacitors and specialized dielectric structures—could produce a propulsive force not fully reducible to conventional aerodynamics or electromagnetism. Over the course of his life, Brown filed patents, pursued investors, and intermittently sought military and industrial sponsorship for “electrokinetic” propulsion devices. In ufology-adjacent culture, Brown became an archetypal “breakthrough” figure: a technically fluent experimenter whose claims are interpreted either as a neglected path toward field propulsion or as a well-publicized misunderstanding of ion-driven thrust.

Background

Brown emerged in an era when electricity, radio, vacuum tubes, and early high-voltage experimentation were still culturally associated with frontier science. He developed interests in the relationship between electricity, dielectric materials, and force production, and he sought conceptual parallels between electrical polarization and gravitational behavior. Brown’s early work is frequently discussed in connection with Dr. Paul Alfred Biefeld, a physicist whose name became attached to Brown’s effect; however, the degree and nature of Biefeld’s direct collaboration is often portrayed differently across accounts. What is clear is that Brown’s formative period combined hands-on experimentation with a willingness to push interpretation beyond conservative engineering models.

Ufology Career

Brown was not a ufologist in the strict sense of investigating sightings or interviewing witnesses. His place in ufology arises from the persistent claim that UFO-like performance would require propulsion and inertial behavior beyond conventional aircraft—and that Brown’s work provides a plausible technological pathway. Over time, Brown’s name became embedded in “electrogravitics” lore: the idea that gravity-like forces might be engineered through electrical means. As a result, Brown is frequently invoked in narratives about hidden aerospace breakthroughs, classified propulsion programs, and the supposed technological underpinnings of advanced craft.

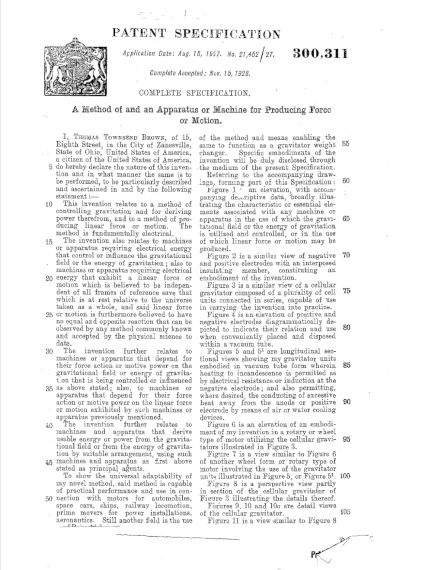

Early Work (1923–1939)

Brown’s early period is typically described as the era of first observations and demonstrations. He experimented with high-voltage capacitive assemblies—often with asymmetrical geometries and heavy dielectric loading—and reported directional thrust toward one electrode. Brown interpreted these results as evidence of a coupling between electric fields and gravitational-like forces. This phase also established his lifelong pattern: build demonstrators, record effects, patent device architectures, and articulate a theoretical story that framed the apparatus as accessing a deeper physical interaction than standard electromagnetism.

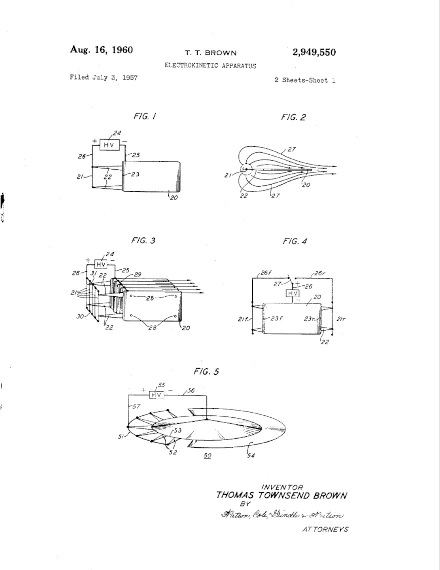

Prominence (1940–1959)

During the mid-century period, Brown’s ideas gained broader visibility through patents, proposals, and periodic mention in popular and semi-technical venues. In accounts sympathetic to Brown, this is framed as the peak period of institutional curiosity, when military or aerospace stakeholders allegedly examined “electrokinetic” concepts for potential propulsion applications. In skeptical readings, this period reflects a recurring cycle of ambitious claims and demonstrations that did not translate into reproducible, transformative technology. Regardless of interpretation, by the late 1950s Brown had become one of the most cited names in the emerging “antigravity” subculture, serving as a living bridge between laboratory tinkering and speculative aerospace dreams.

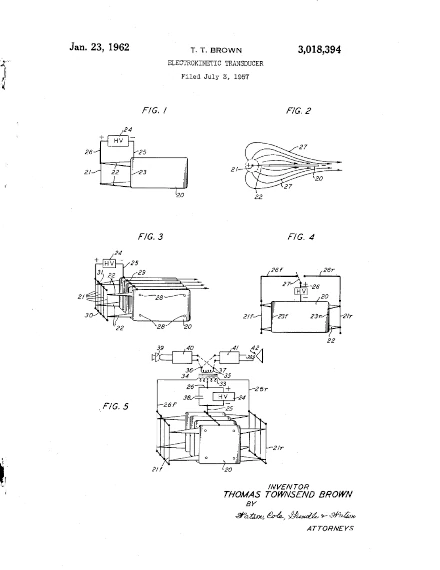

Later Work (1960–1985

Brown’s later years saw continued advocacy, refinement of device designs, and persistent attempts to secure funding and validation. The broader scientific environment became less receptive to the “gravity control” framing as conventional plasma physics and electrohydrodynamics provided strong alternative explanations for many high-voltage thrust demonstrations—particularly in air, where ion wind can generate significant force. Yet in fringe-propulsion circles, Brown’s status solidified: he was increasingly remembered not only for what he achieved, but for what his supporters believed he nearly unlocked—and what they suspected might have been quietly absorbed into classified research pipelines.

Major Contributions

- Electrogravitics as a cultural/technical framework: Brown helped define the vocabulary and “engineering imagination” of electrically driven gravity-like propulsion.

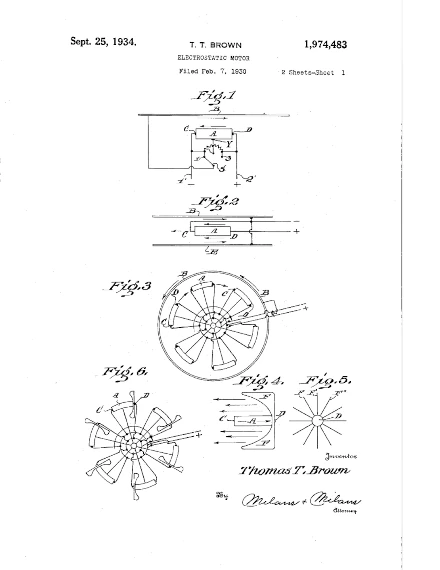

- Capacitor-as-thruster experimentation: sustained, decades-long demonstration work linking high-voltage dielectric systems to measurable thrust effects.

- Patent and proposal trail: a durable public record of device architectures and claims that later researchers and enthusiasts repeatedly mined and reinterpreted.

Notable Cases

Biefeld–Brown demonstrations: Brown’s best-known “case” is the repeated observation that asymmetrical capacitor structures under high voltage can produce a directional force. In supportive narratives, this is treated as an early glimpse of gravity control; in skeptical narratives, it is treated primarily as electrohydrodynamic thrust (ion wind), especially under atmospheric conditions.

Electrokinetic apparatus proposals: Brown’s broader portfolio included multiple designs aimed at increasing thrust and controllability through dielectric selection, electrode geometry, and excitation methods. These proposals became templates for later “lifter” devices and electrohydrodynamic hobbyist experiments, even when the underlying physics was explained without invoking gravity coupling.

Views and Hypotheses

Brown’s core hypothesis was that strongly polarized dielectrics under high electric stress could interact with matter in a way that resembles a gravity-like force. He treated electric field gradients, dielectric polarization, and device asymmetry as the keys to producing net thrust. He often implied that the effect was not merely a wind or corona phenomenon, but a deeper field interaction—sometimes framed as a modification of gravitational coupling or a new force channel accessible via electromagnetic excitation.

Criticism and Controversies

Brown’s legacy is inseparable from the “what is the thrust?” dispute. Many experimental replications demonstrate that in air, high-voltage asymmetric capacitors can produce thrust through ionization-driven airflow (electrohydrodynamics). This provides a strong conventional explanation for much of the effect in atmospheric conditions. The hardest question—whether any residual “non-ion-wind” component persists in vacuum or controlled environments—has been debated for decades, with claims and counterclaims often complicated by experimental artifacts, measurement challenges, and the tendency of enthusiasts to over-interpret partial results.

Another recurring controversy involves “suppression” narratives: Brown is frequently positioned as a victim of secrecy, with claims that institutions quietly confirmed the effect and buried it. Critics note that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof and that a lack of robust public demonstrations limits how far such narratives can be responsibly taken.

Media and Influence

Brown’s influence is vast in niche propulsion culture. He is cited in electrogravitics literature, invoked in UFO propulsion arguments, and referenced in countless discussions about “field drives,” inertial modification, and antigravity. Popular media treatments often present him as a romantic figure—a lone inventor nearing forbidden knowledge—while technical skeptics present him as a case study in how high-voltage phenomena can be misread when experimental controls are weak or when interpretation outruns measurement.

Legacy

Thomas Townsend Brown’s legacy operates on two levels. Technically, his work is part of the historical lineage that helped popularize electrohydrodynamic thrust devices and inspired generations of experimenters to explore the behavior of high-voltage capacitors and plasmas. Culturally, he is a foundational saint of electrogravitics: a name that anchors claims that “UFO-like propulsion has been on the table for a century.” Whether one sees Brown as visionary or mistaken, his imprint on the mythology and experimentation culture of unconventional propulsion is permanent.

Documentaries

The CIA Scientist Who Built UFOs Before Bob Lazar (Townsend Brown Documentary)

(2024)

American Alchemy

youtube.com/@JesseMichels

Gravity Buster T. Townsend Brown: The Man, Myth and Legend!!!

(2024)

The Cosmic Summit

youtube.com/@cosmicsummit

The Man Who Mastered Gravity: Life and work of Thomas Townsend Brown with Paul Schatzkin

(2024)

Out of India Theory

youtube.com/@outofindiatheory

Papers

The Scientific Notebooks of Thomas Townsend Brown - Volume 1

rexresearch.com/brown1/brown1.htm

The Scientific Notebooks of Thomas Townsend Brown - Volume 2

rexresearch.com/brown2/brown2.htm

The Scientific Notebooks of Thomas Townsend Brown - Volume 4

rexresearch.com/brown4/brown4.htm

The Montgolfier Project

uapedia.wiki/pdfs/Montgolfier Project.pdf