UAP Personalities

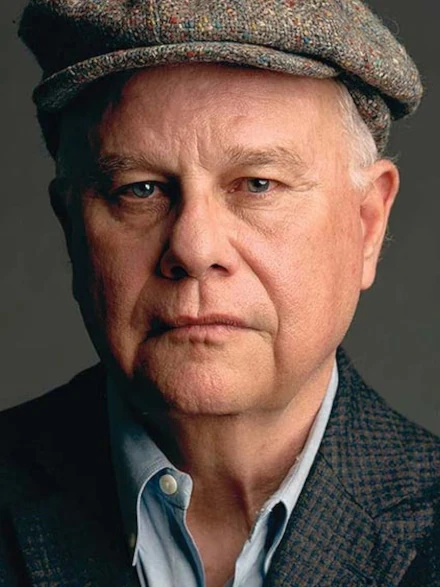

Strieber, Whitley

TL;DR Claim(s) to Fame

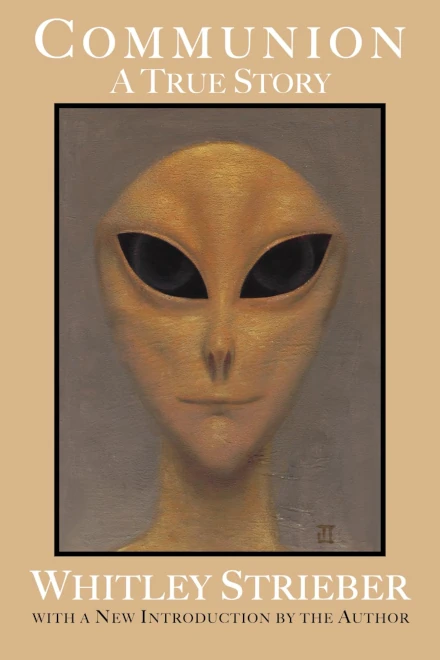

- Authored Communion, the landmark “visitor/abduction” narrative that defined late-20th-century alien imagery.

- Popularized the modern abduction template: missing time, bedroom visitations, and lifelong “contact” arcs.

- Built a long-running media ecosystem (talk shows, interviews) sustaining “high strangeness” discourse.

- Criticized for blending memoir, hypothesis, and metaphor—making evidentiary evaluation difficult.

Introduction

Whitley Strieber is an American author whose writings became central to the late-20th-century “abduction era” of ufology. Unlike investigators focused on external sightings and physical traces, Strieber’s influence derives from first-person narrative: claimed experiences with “visitors” that blend memory, fear, intimacy, and existential uncertainty. His work helped set the emotional and visual vocabulary of abduction culture—especially through the iconic “grey” imagery that became inseparable from UFO popular imagination.

Background

Strieber was already a successful writer before his UFO-related works, with a career spanning fiction and mainstream publishing. This literary background shaped how his UFO books were received: supporters saw a skilled narrator able to articulate ineffable trauma; critics saw a storyteller whose craft could transform ambiguous experiences into compelling myth.

Ufology Career

Strieber’s ufology career is primarily autobiographical and interpretive. He is not known as a case investigator in the classic sense, but as a cultural node—an author whose public disclosures catalyzed widespread discussion of abduction experiences and influenced how other experiencers described their own encounters. He also became an interviewer and host figure, curating a platform for high-strangeness discourse.

Early Work (1985-1989)

Strieber’s early UFO prominence centers on the emergence of Communion and the public debate it triggered. The book’s impact was amplified by its mainstream visibility and by the way it reframed UFO encounters as psychologically invasive, ambiguous, and deeply personal rather than simply “lights in the sky.”

Prominence (1990-2005)

During the peak abduction era, Strieber’s work became both a reference point and a lightning rod. Many experiencers reported that his descriptions matched their own, while skeptics argued that cultural contamination could cause later accounts to echo a popular template. Strieber’s continued publications expanded the narrative arc into themes of hybridization, spiritual transformation, and an ongoing relationship with the unknown.

Later Work (2006-2025

In later years, Strieber continued producing content that blended UFO themes with broader high-strangeness interests. His role shifted toward elder-statesman of experiencer culture—less about proving a claim and more about interpreting what the experiences mean and how they alter identity, belief, and worldview.

Major Contributions

- Defined mainstream abduction-era imagery and emotional vocabulary.

- Legitimized “experiencer testimony” as a major ufological data stream.

- Built a sustained media platform for high-strangeness conversation.

Notable Cases

Strieber’s central case is himself: the suite of experiences described across Communion and its sequels. His “notable” contribution is not a single event but a persistent narrative arc that influenced countless later accounts.

Views and Hypotheses

Strieber’s interpretations have ranged from literal nonhuman contact to more complex models that incorporate consciousness, symbolism, and unknown dimensions of mind. He often treats the phenomenon as ontologically ambiguous—real in impact and pattern, but resistant to clean categorization as purely physical or purely psychological.

Criticism and Controversies

Critics argue that Strieber’s work is not falsifiable and that memory-based narratives—especially those involving missing time and dreamlike experiences—are vulnerable to confabulation, sleep phenomena, and suggestion. Supporters respond that the consistency of experiencer reports and the enduring intensity of the accounts suggest a genuine phenomenon requiring new conceptual tools.

Media and Influence

Strieber is among the most influential UFO media figures of the modern era. His books, interviews, and hosted discussions shaped public expectations about what alien contact looks and feels like.

Legacy

Strieber’s legacy is cultural and conceptual: he helped move ufology toward experiencer-centered inquiry and ensured that abduction narratives became a permanent pillar of UFO discourse, regardless of where one lands on their literal truth.