UAP Personalities

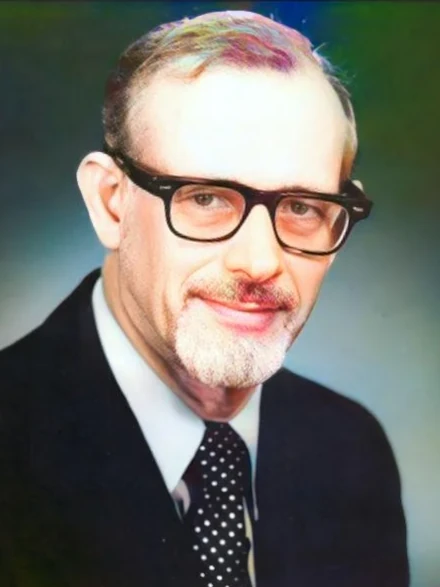

Stringfield, Leonard H.

TL;DR Claim(s) to Fame

- Pioneered systematic compilation of alleged UFO crash/retrieval accounts via his “Status Report” series.

- Argued that recovery stories predate Roswell pop culture and form a persistent hidden-history pattern.

- Influenced the modern crash-retrieval canon by preserving insider claims and rumor chains in print.

- Criticized for reliance on anonymous sources and for elevating unverifiable testimony to quasi-archival status.

Introduction

Leonard H. Stringfield was an American UFO researcher best known for compiling and preserving accounts of alleged UFO crashes and recoveries. While many ufologists focused on sightings and radar-visual incidents, Stringfield specialized in a controversial subgenre: testimony and rumor about downed craft, recovered materials, and alleged bodies. His impact on ufology is difficult to overstate because later crash-retrieval narratives—both serious and sensational—often trace lineage through the categories and claims he collected.

Background

Stringfield’s credibility within ufology was shaped by his long involvement with UFO organizations and his reputation as a committed archivist. He cultivated sources and built files over decades, positioning himself as a steward of material that conventional historians either could not access or would not take seriously.

Ufology Career

Stringfield’s career combined organizational involvement with a growing specialization in crash-retrieval narratives. He was a networker and compiler: he gathered testimony, compared versions, tracked dates and locations, and attempted to separate repeating patterns from one-off rumors. His “Status Reports” became a recognizable format—serial publications that updated the community on new claims, new leads, and reinterpreted older stories.

Early Work (1952-1976)

In the early decades of modern ufology, crash stories circulated episodically but lacked stable bibliographic form. Stringfield’s early work helped normalize the idea that such stories could be cataloged and treated as a distinct research domain. He also engaged with broader UFO organizational life, which gave him access to witnesses, investigators, and rumor streams.

Prominence (1977-1994)

Stringfield’s prominence peaked with his crash/retrieval focus. The “Status Report” series crystallized his role as the keeper of a shadow archive. Even researchers who doubted the claims often read Stringfield to understand how the crash-retrieval ecosystem functioned: who was talking, what was being alleged, and how the narrative network evolved.

Later Work (1995-1999

As Roswell culture expanded and crash-retrieval talk became mainstream within UFO media, Stringfield’s earlier catalogs gained renewed attention. His late career is often framed as the moment his lifetime of compilation became foundational infrastructure for a new generation of writers, whether as source material or as a cautionary example of how rumor can become “history.”

Major Contributions

- Created a durable crash-retrieval literature format through serial Status Reports.

- Preserved testimony streams that might otherwise have been lost to oral history.

- Influenced the structure of later crash-retrieval narratives by naming categories and patterns.

Notable Cases

Stringfield’s “notable cases” are often clusters rather than single events:

- Alleged pre-Roswell recoveries and “early era” retrieval rumors.

- Accounts involving purported bodies, storage, and transport narratives.

- Roswell-adjacent claims treated as part of a wider recovery pattern.

Views and Hypotheses

Stringfield argued that the persistence and internal consistency of many recovery stories suggested an underlying reality, even if individual accounts were imperfect. He treated anonymous sourcing as unavoidable given secrecy claims and emphasized triangulation through repetition: if similar claims emerge independently, they deserve attention.

Criticism and Controversies

The primary criticism is epistemic: anonymous sources and unverifiable testimony cannot be independently tested, and repetition can result from cultural contamination as easily as from truth. Critics argue that compiling claims can inadvertently launder rumor into authority. Supporters counter that secrecy conditions force researchers to work with partial data and that systematic compilation is better than letting the stories drift unrecorded.

Media and Influence

Stringfield’s influence is strongest in crash-retrieval circles and documentary projects tracing the genealogy of retrieval claims. He is frequently cited as a “proto-architect” of the retrieval subculture.

Legacy

Stringfield’s legacy is double-edged: he preserved a controversial shadow archive that became foundational to crash-retrieval mythology, while also exemplifying the methodological hazards of building history from testimony under conditions of alleged secrecy.