UAP Personalities

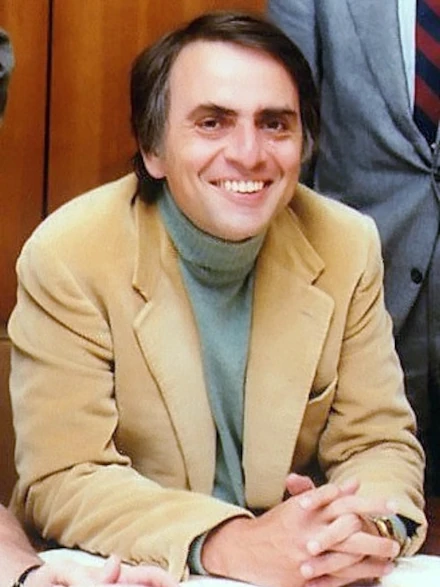

Sagan, Carl

TL;DR Claim(s) to Fame

- Championed scientific skepticism applied to UFO claims while arguing the topic merited study due to public interest.

- Popularized the logic of “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” in UFO and paranormal contexts.

- Critiqued reasoning errors and evidentiary weaknesses in UFO/abduction discourse in widely read books and lectures.

- Helped shape the mainstream scientific posture: investigate reports rigorously, but avoid unwarranted conclusions.

Introduction

Carl Sagan was an American astronomer and one of the most influential science communicators of the twentieth century. Within UFO history he occupies a distinctive role: not a field ufologist, but a primary architect of the modern scientific attitude toward UFO claims. Sagan combined a willingness to consider extraterrestrial life plausible in the universe with a strong insistence that UFO conclusions demanded disciplined evidence. His writing and public lectures trained multiple generations to separate curiosity from credulity—making him central to the “skeptical ufology” tradition even as he remained outside UFO organizations.

Background

Sagan’s scientific career in planetary science and astrobiology positioned him as a credible voice on the likelihood of life elsewhere. This credibility mattered culturally: audiences who were already fascinated by UFOs often treated astronomers as natural authorities on the “alien question.” Sagan recognized that the UFO topic functioned as a public classroom for critical thinking. Rather than treating the subject as beneath attention, he used it as a demonstration arena for how science handles uncertainty, error, and the temptation to leap beyond the data.

Ufology Career

Sagan’s ufology “career” was a career of commentary, pedagogy, and boundary-setting. He did not build case files or lead investigations; instead he critiqued the logic and methods used in UFO argumentation, pressed for reliable instrumentation, and encouraged scientists to engage the question without surrendering standards. His engagement also included private and semi-public dialogue with UFO researchers and writers, treating them as interlocutors rather than as automatic adversaries.

Early Work (1947-1969)

As a young man in the early “flying saucer” era, Sagan expressed interest in what UFO reports might imply, including questions about governmental response if reports proved extraterrestrial. This early curiosity matured into a methodological stance: the correct posture was neither reflexive belief nor reflexive contempt, but careful triage—separating misidentifications, hoaxes, psychological effects, and rare unexplained events without inflating the last category into a conclusion about alien visitation.

Prominence (1970-1996)

Sagan’s prominence in UFO discourse peaked through his books and media presence, where he repeatedly used UFOs and abduction narratives as examples of how humans misperceive, misremember, and misinfer. In this period he helped normalize a key principle: a claim’s popularity is not evidence. He also emphasized the need for reproducible, high-quality data—clear chain of custody for materials, calibrated sensors, and transparent methods—before extraordinary interpretations could be taken seriously.

Later Work (1997-2025

After Sagan’s death, his UFO influence only expanded. His phrasing and logic became embedded in skeptical organizations, science education, and mainstream journalism, shaping how new waves of UFO reporting are interpreted. In the modern UAP era, Sagan is frequently invoked by both sides: skeptics cite him to demand higher evidence thresholds, while some UFO advocates cite his willingness to “study the phenomenon” as validation that interest itself is not irrational.

Major Contributions

- Critical thinking framework: Made UFOs a public case study in epistemology, error, and the scientific method.

- Evidence standards: Reinforced the demand for reproducible, transparent proof before adopting extraordinary conclusions.

- Bridge role: Demonstrated that one can take the public fascination seriously without endorsing weak claims.

Notable Cases

Sagan is not tied to a single signature UFO case. His “casework” is conceptual: the systematic critique of how cases are argued and the identification of recurring reasoning failures in UFO and abduction narratives.

Views and Hypotheses

Sagan treated extraterrestrial life as plausible in the cosmos while remaining skeptical that UFO sightings demonstrate visitation. He argued that many reports can be explained by misperception, cultural contagion, hoaxing, and the human drive for narrative closure. However, he also maintained that the public interest and the existence of some unexplained reports made disciplined study worthwhile—provided conclusions were proportionate to evidence.

Criticism and Controversies

From within ufology, Sagan was criticized for being too dismissive of “best cases” and for emphasizing debunking logic over field engagement. From some scientific skeptics, he was occasionally criticized for conceding too much legitimacy by urging study. Yet this tension captures his enduring position: Sagan represented a middle stance—open inquiry without epistemic surrender.

Media and Influence

Sagan’s media reach ensured that his framing of UFOs became default “common sense” for mainstream audiences. His impact is visible in journalism norms (requests for evidence, chain of custody, corroboration) and in the broader cultural expectation that “alien” is an extraordinary conclusion, not a starting assumption.

Legacy

Sagan’s legacy in ufology is foundational: he helped define the intellectual hygiene that serious discussion requires. Even among those who disagree with his conclusions, his standards remain a reference point for what it would mean to actually prove—rather than merely proclaim—an extraterrestrial hypothesis.

Books

Non-Fiction

TV Shows

Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (1980)

https://archive.org/details/cosmos_1980

https://cosmicperspective.com/carl-sagan-cosmos/