UAP Personalities

Keyhoe, Donald

TL;DR Claim(s) to Fame

- Key mid-century UFO advocate who argued for the reality of UFOs and for government transparency.

- Led NICAP and helped build a disciplined “pressure group” model for civilian UFO activism.

- Popularized the claim that official secrecy distorted public understanding of UFO evidence.

- Criticized for over-interpreting limited data and for treating institutional interest as evidentiary confirmation.

Introduction

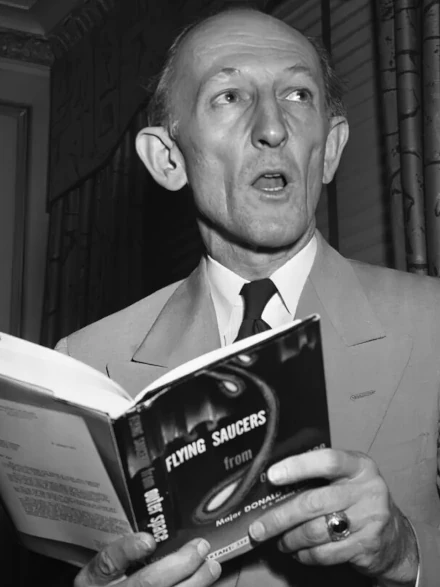

Donald E. Keyhoe was an American former Marine Corps aviator and influential UFO advocate whose work helped define mid-century civilian ufology as a political and institutional accountability project. He is best known for his leadership of NICAP (National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena) and for arguing that UFOs represented a real phenomenon that the U.S. government was minimizing or concealing.

Background

Keyhoe’s aviation and military background gave him credibility with audiences inclined to trust trained observers and official procedures. He approached UFOs not as occult mysteries but as an aeronautical and national-security issue, emphasizing the stakes of airspace intrusion and the importance of honest governmental communication.

Ufology Career

Keyhoe’s ufology career combined authorship, public advocacy, and organizational leadership. He helped transform ufology into a structured civic project: collect credible reports, press officials, and demand oversight. This made him an early prototype of the “disclosure advocate,” though in a more procedural and less sensational register than later eras.

Early Work (1950-1955)

In early work, Keyhoe entered public UFO discourse through widely read publications and books that framed UFOs as a real, unresolved airspace problem. He emphasized credible witnesses and argued that dismissive explanations failed to account for a subset of reports.

Prominence (1956-1969)

Keyhoe’s prominence peaked through NICAP leadership and sustained media engagement. He positioned NICAP as a serious, document-oriented organization capable of engaging Congress, the military, and the public. His efforts helped make UFOs a policy-adjacent topic rather than mere popular entertainment.

Later Work (1970-1988)

In later years, Keyhoe’s influence persisted through the institutional memory of NICAP and through continued citation in debates about secrecy and oversight. Even as ufology diversified into abduction and high-strangeness schools, Keyhoe remained emblematic of the “national security and transparency” approach.

Major Contributions

- NICAP leadership: Helped create a disciplined organizational model for civilian UFO advocacy.

- Policy framing: Positioned UFOs as a legitimate oversight and national-security topic.

- Credibility emphasis: Elevated the role of trained observers and official documentation in public argument.

Notable Cases

Keyhoe engaged many mid-century reports and treated clusters of credible sightings as a cumulative case. He is less tied to a single incident than to an argument about the overall pattern: repeated credible reports, inconsistent official explanations, and a persistent unknown residue.

Views and Hypotheses

Keyhoe strongly favored the view that UFOs were real objects, plausibly representing advanced technology, and that government agencies possessed more information than they disclosed. He framed this as both a public-right-to-know issue and a security concern.

Criticism and Controversies

Critics argue that Keyhoe sometimes extrapolated beyond the strength of available data and that secrecy claims can become self-sealing. Supporters argue that his push for oversight was rational given the inconsistency of official messaging and the repeated presence of credible witnesses.

Media and Influence

Keyhoe’s influence was substantial in print and broadcast media during ufology’s formative public decades. His work helped normalize the idea that UFOs could be discussed seriously, and his organizational strategies anticipated modern advocacy campaigns.

Legacy

He remains one of the most important early civilian leaders in ufology, remembered for professionalizing advocacy and for shaping the long-running narrative that official secrecy is central to the UFO problem.